The Unbearable Nonsense of Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Identities

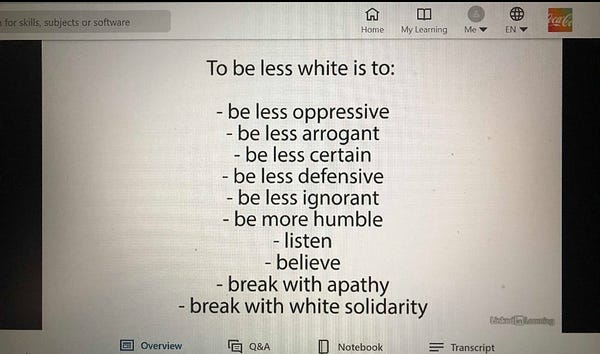

Recently, the Coca-Cola Company was in the news because someone there leaked screenshots from a training seminar given to employees, a seminar entitled “Confronting Racism: Understanding what it means to be white, challenging what it means to be racist.” The seminar is available to anyone—for a fee—on LinkedIn’s Learning platform. It’s given by noted race merchant Robin DiAngelo. Here’s where the story broke—on Twitter, of course—with some screenshots of the seminar:

To be less white is to be…less oppressive…less ignorant. Who can argue with that? It’s a truth bomb, amirite?

Sarcasm aside, I don’t mean this to be about the abject stupidity of DiAngelo’s “white fragility” theory and its correspondingly ignorant ideology. Kudos to her, I guess, for finding an angle that boatloads of suckers are willing to accept and pay her to teach them. It’s just another grift, at the end of the day. But embedded in her theory, in what is termed “identity politics,” is a proposition that many people simply accept out of hand: that one’s ancestral history is an important aspect of one’s actual existence, that this history says something important about who one is.

When I say “ancestral history,” I am referring to a collection of things, including—but not limited to—perceived “homelands” for one’s ancestors, the race or ethnicity of these ancestors, their cultural practices (especially ones that seem unique) and customs, their religious and/or spiritual beliefs, and their assumed abilities and capabilities, especially ones that can be cast as impressive and/or unusual. People may know all of these things about themselves and their ancestors or only some of them, they may try to learn more about them and even apply the science of genetics to discover some of the above (based on the actually faulty assumption that if one shares the genetic make-up of, say, people who inhabited Lapland, one’s ancestors were not only reindeer herders, but also really good reindeer herders).

To use myself as an example, I know that some of my ancestors—on my father’s side—arrived in what is now the United States in the latter part of the 17th century, having come from Scotland. And I know than I share some genetic markers with the Gaels. Based on this knowledge, I could draw a lot of conclusions—all fundamentally wrong-headed—about who I am, why my personality is what it is. For instance, I might decide that my libertarian leanings are a product of my family being in the United States since before the Revolutionary War, that this fact means I am a special kind of person, a natural “American patriot,” as it were. And I might further decide that this natural patriotism, this aversion to royalty and oppressive government comes from my Scottish and Gaelic heritages, as well, where clans were a dominant feature of the social and political hierarchies. I might even decide that wearing a kilt with my clan’s tartan pattern is something that I need to do, because it indicates who I am, along with celebrating Gaelic and Scottish specific holidays. And of course, I can rationalize that my affinity for single malt Scotch as an hereditary thing, perhaps even assuming that my palate—when it comes to Scotch—is superior to that of most other people, I can scoff at them when they order expensive single malts in bars since I know that can’t really appreciate what it is they are drinking, at least not in the ways that I—a true Scotsman—can.

All of the above I can think and do freely, given that I’m not hurting anyone else. Though I think assumptions about patriotism and the like based on when one’s family came to this country are totally untenable ideas; there’s no valid argument to justify them. And my special ability to enjoy Scotch is not based on any sort of legitimate science, it’s a totally fantasy that I have concocted in my mind. Still, me thinking such these things is not something that can be simply disallowed, anymore than it can be disallowed for someone with Native American ancestry to believe that this makes them excellent trackers, or that it makes the true “original Americans,” as compared to people with no such ancestry.

Do I need to say that again?

The fact that I have ancestors who lived in Scotland doesn’t give me any special skills, with regard to things that are generally considered to be “Scottish.” The fact that I can trace my family in the United States back to pre-Revolution days doesn’t make me special in any way, it doesn’t confer on me special rights or privileges of any sort.

Now, if I want to prance around in kilts, if I want to drink Scotch and be snooty about it, if I want to decorate my home with Gadsden flags, tartan throws, and medieval tapestries, that’s my right. Why shouldn’t I be able to do these things? What we are talking about here are choices in style and personal affectations, nothing more. I can manufacture all sorts of reasons for these choices, but at the end of the day that’s all they are. I have no special authority to make them, simply because of who my ancestors were. Such a proposition is…well, it’s stupid.

So—follow me here—if instead of the above choices I made some different ones, that would be okay, too. For instance, I might decorate my home with Japanese prints, with Bonsai trees and Samurai katanas. I might choose to become a connoisseur of sake and to dress in kimonos. Why shouldn’t I, if I find these things pleasing, if acting this way makes me happy?

At the same time, people who see me doing all of this—especially people with Japanese ancestry—might roll their eyes at me, in the same way that I might have rolled my eyes at non-Scottish people enjoying single malt Scotch.

Two different things: first there are those choices made, with respect to various racial, ethnic, or cultural heritages, then there is the attitude expressed towards others for the choices they make in this same regard. While one is free to make these choices and free to feel however they want about the choices others make, I would argue that having an “attitude” about others’ choices is the fundamental issue that has led to our current state of abject stupidity, when it comes to issues of race and culture.

And frankly, in the United States and in Western Europe, this stupidity is partly a consequence of the dominant race or ethnicity being “protectionist,” so to speak, when it comes to their perceived cultural norms. Yes, that’s right, I’m saying “white culture” is a thing and white people historically tried to limit participation in this culture to their own ethnicity, whenever possible.

There was a time—not all that long ago, maybe even yesterday in some places—where a black person on a tennis court or a golf course would draw looks of confusion and disgust from the non-black people—uh, white people—at these places. One can chalk this up to simple racism, to be sure, but I think it can quite obviously be cast as an example of assumed cultural appropriation, as well. The obvious retort to that claim—that white people don’t have a monopoly on playing golf or tennis, not even white people who are Gaelic, because both sports are Gaelic in origin—is 100% correct, in my opinion. And that’s because all claims of cultural appropriation are similarly flawed, are all ultimately nonsense.

At it’s root, the notion of cultural appropriation is based on the assumption that some things are a product of culture. This is wrong. Things—tangible or otherwise—are not created by “culture,” they are created by people, people who might happen to be a part of a given culture, but who are otherwise still people. Disc golf—what I learned as Frisbee Golf—is a sport (or game) that appeared all over the US during the 1960’s and 1970’s. No one can claim to have invented it, but there are certainly a number of people who can claim to have been pioneers of the sport. And these people can all be fairly characterized as members of US culture, I think. So, is disc golf a cultural activity? Are people in Brazil who play disc golf engaging in cultural appropriation? No and no, quite obviously, I think. People created the concept of disc golf, other people liked, so they began playing, still others thought of different ways to play it and sometimes modified it, changes which were then either accepted or rejected by still other people. That’s how it developed into its generally accepted form that is played all over the world.

A similar story can be told about most every “cultural” practice or product. Change “disc golf” to “tacos” and the above story still works, only with Mexico as the place of origin. Many people like tacos, people all over the world. There is no cultural ownership of the concept, because tacos weren’t created by a culture, they were created by specific people, most of whom are now lost to time.

People often need the crutch of their heritage as a means of finding there place in the world, just as they often need the crutch of religion. There’s nothing wrong with theses things, they’re a means of establishing and maintaining a community, after all. The problems arise when such things are used to divide and exclude, especially by people who can exercise some measure of authority over others. We need to recognize that no cultural, racial, or ethnic group owns or has a right to specific styles, to specific practices, to specific foods, etc. And the way to recognize this is to accept that people are not defined by who their ancestors were (or who they thought their ancestors were, actually; people get it wrong all the time).

That said, if you need me to tell you how to appreciate good Scotch, I’m happy to do so…